..The remains of shielings and keeils above Sulby Glen attest to the mountain valley’s mediaeval use as summer pasturage for livestock, when the animals would be driven onto the high hills to graze while the families who tended them would live in temporary summer dwellings and dig peat for winter fuel.

By the late 17th century more permanent farms were built on ’intack’ land enclosed from the surrounding mountain waste with permission from the Stanley Lords of Mann.

One example was The Close, owned by the Cowley family and perched on the heights overlooking the ’Great River’, as the Sulby - the island’s longest - was known.

With hard work the peaty soil could be adapted to grow rye, barley and oats and barns were constructed from the local slately rock for storage of the harvested crop, as well as round stone bases to keep haystacks out of the mud.

Animals were coralled in stone enclosures nearby - it is believed that the very name Tholt-y-Will is a corruption of the Manx Gaelic Tolta-y-Woalilee, ’the hill of the cattle fold’ - and the farmhouse would have been roofed with a weighted ’suggane’ thatch.

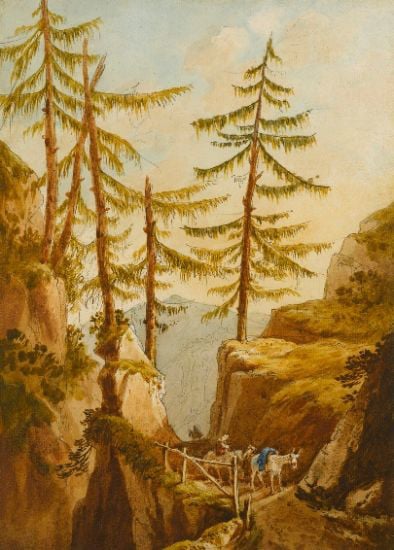

Curiously enough, although later promoters of the area as the ’Manx Switzerland’ probably would not have realised it, this development paralleled the story in the Swiss Alps, where the stone-based and wooden upper-storeyed chalets were originally summer dwellings occupied when livestock was driven to upper pastures after the winter snows had melted (a continuing tradition known as Alpine transhumance), but later, over time, became year-round homes clustered in scattered villages.

Indeed, the very word Alps is derived from the German word for a seasonal mountain pasture.

While, by contrast, many of the Sulby area’s mountain farms are now ruined tholtans after their occupants moved to less arduous ways of life elsewhere, by the 19th century the valley’s scenery was attracting summer visitors of a different kind.

As early as 1825 Douglas resident Mr T Ashe’s A Manx Sketchbook tourist guide, with illustrations by bishop’s wife Lady Sarah Murray, extolled the delights of Sulby Glen to early tourists: ’This region, on the borders of the road from Kirk Michael and Ramsey, is the most enchanting spot on the Island, and a singularly rich one... The scenery here is highly diversified. The ground is well covered with trees and shrubs, apparently all planted. The valley winds considerably... Swelling grounds, cultivated hills, naked rocks, variegated groves and falling waters, present themselves to view in stages rising above each other, till mountains clustering together in the back-ground shut up the scene.’

Fifty years later Jenkins Guide of 1874 informed visitors: ’It is a delightful drive from Ramsey to the Sulby village, at the entrance to the glen. From the village the road passes by a starch-mill and runs up the glen at the base of Mount Karrin, and by the side of the river, with the Carrick mountain on the left, and in front Slieu Monagh.

Every object around is extremely beautiful, and perhaps in no part of the island are the hills more finely grouped.

’The tourist presently finds himself in a secluded vale, surrounded by high mountains, and discovers that he is approaching a most hilly country, and a spot worthy to take rank with some of the most attractive of the hills and dales of the sister isles.

’After making a sharp turn to the right and passing a few farmsteads, another reach of the glen, a mile in extent, is displayed, where the road runs by the side of a stream, whose bed is strewn with boulders of quartz and slate rock; and the mountains, covered with gorse, heather, and grass, rise so sheer on either hand as only to allow room for a tiny plot of ground on one side of the brook.

’At another sharp turn the lower part of the vale disappears, and the scene becomes in the highest degree wild and solitary. A view is caught of the summit of Snaefell. On the brink of the river are two or three cottages, tenanted by the families of men employed in the adjoining slate quarry. High hills are on every hand, with the stream forming cascades and flowing over boulders and ledges of rock at the traveller’s feet, and all around are tiny rills trickling musically down the mountain sides.

’Another turn reveals a pleasant portion of the glen, containing a small larch plantation, and at the head a Methodist chapel, close to the Dockspout Bridge (sic - it’s actually Droghad-y-Cabble: Chapel Bridge) which crosses the stream.

’A cottage close to the bridge is said by the residents to be the oldest house on the island... Close to the chapel, on the opposite side of the stream, is a small but prettily wooded gill leading in the direction of Snaefell, and a notice-board warns strangers that they may not enter without leave from the people living on the adjoining farm of Ballaskella, perched on the hill above. Picnic parties sometimes spend the day here.’

The reference to the starch mill refers to an industry which flourished briefly in the valley from the 1850s to the end of the 19th century and even supplied Queen Victoria with this product helping to keep the voluminous quantities of silks and linen worn by women of the period standing upright and outwards over crinoline hoops as it was meant to. The mill had originally been for woollens and was owned by the Southwards family, who installed a new waterwheel in 1831 but then moved to a different mill a few years later. The use for starch, with ownership by an English family, first appears in records of 1851, with the product being made from potatoes, with 50 tons of spuds being processed each day as well as maize for the manufacture of cornflour at the same premises. Foreign imported alternatives and changing fashions eventually led to its closure. It briefly became a woollen mill becoming a filter plant for the Northern Water Board in 1935. The building still stands today.

Quite when the label the ’Manx Switzerland’ was added to the area, and by whom, is unclear but having been absent from Jenkins Guide’s 1874 description it was actively being used to promote the area by 1899 when an account of the Manx Northern Railway appeared in the Railway Magazine that year. The author tells us: ’Six miles west of Ramsey, on the MNR, and about the centre of the northern face of the mountains, is Sulby Glen - the ’Manx Switzerland... Conveyances ply regularly between Sulby Glen station and the Glen, and also between St John’s station and Glen Helen and Glen Meay’.

He adds that fishermen find the River Sulby the finest for their sport in the island and the road was enjoyable for cyclists too.

Soon there was another way to reach the glen’s beauties - by taking the Manx Electric Railway to Laxey, then the Snaefell Mountain Railway to Bungalow and wagonettes would take you down into the glen to the Tholt-y-Will waterfalls. It is interesting that Edward Alan Christian, the last of the male members of the family to live at Milntown, actually trained as an electrical engineer in Switzerland, where the country was a pioneer in the new technology due to its lack of coal but presence of plenty of rivers to harness for hydro-electric power.

He took his skills first to the new electric railways on the island before then moving on to helping convert the Mersey Railway to electricity after the public complained of steam engine smoke in its long tunnels. Sadly he became seriously ill and died at Milntown aged just 38.

By the Edwardian era it was motor charabancs which met the trams at the Bungalow and took people to Tholt-y-Will and by 1926 the MER had actually bought the glen and was running the tearoom at Tholt-y-Will, which had been built in 1907.

The MER advertised conducted tours of the Manx Switzerland, along with its many other glen attractions at Dhoon, Ballaglass and Garwick, etc with the charabancs taking visitors to the top of the glen where they could ramble down past the waterfalls to the tearoom, enjoy an included lunch, and then be taken down the length of the spectacular valley and onwards to Ramsey to catch their tram back to their starting point. A num ber of photographers set up stalls partway down the valley where they invited the charabanc passengers to have group photographs taken by a sheepfold in the valley - possibly because the area was one of those associated with the folk tale of the Fynoderee volunteering to look after a farmers loaghtan sheep and then chasing a hare for most of the night, thinking it was one of the sheep. There was also a tale further up the valley that a big white boulder on the hillside had been pushed there by a Fynoderee.

The charabancs must occasionally have been driven at a furious pace, as there is a on the Manx Notebook website of two brother cyclists going to consult a fortune teller in Sulby Glen on the eve of one of the men proposing marriage to his girlfriend.

The fortune teller was reluctant to oblige and handed the brother concerned a note which was not to be opened until the next day. On the way home the brothers were run down by a charabanc and the man with the note was killed. When the note was opened it read: ’The will be no tomorrow’.

In 1952 Tholt-y-Will was the first glen to be bought for the nation from the MER for £2,250, excluding the hotel and its grounds.

The hotel was subsequently run by Lord and Lady Strange, who only escaped from the building when it caught fire in 1983 thanks to their Doberman dog Jake waking them up.

Despite being attended by fire engines from Ramsey, Peel, Douglas and Kirk Michael the building was destroyed, going the same way as the original chalet type hotels and restaurants at Laxey station (1917), Dhoon Glen (1937) and Glen Helen (also 1983).

The rebuilt Tholt-y-Will House was built in an authentic Swiss chalet style both inside and out, though in 2013 a grey-painted makeover and new windows and balconies to the upper storey rather robbed it of some of its Alpine charm. Until recently it was a self-catering holiday home but recently it was on the market.

Meanwhile, the glen paths recently suffered closures due to the ravages of larch dieback and signage that confused visitors about what was open and what was not. Let us hope this beautiful glen is soon fully restored.

The nearby Teabarn has been getting rave reviews on Trip Advisor and perhaps all the glens with waterfalls need to be given more promotion, as they once were.

Perhaps in this year of the Manx Electric Railway’s 125th anniversary the ’Manx Switzerland’ tour could be given an occasional revival, and perhaps the access the line gives to other glens needs to be pushed so that trams don’t run nearly empty north of Laxey. As Julia Bradbury recently showed on TV, the area is a wonderful walkers’ paradise with so much to beauty and history to explore.

.png?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.