After my piece a couple of weeks ago about characters around Douglas quayside I was contacted by Joleen Ryan from the Lee family which I mentioned in relation to the lifeboat and fishing.

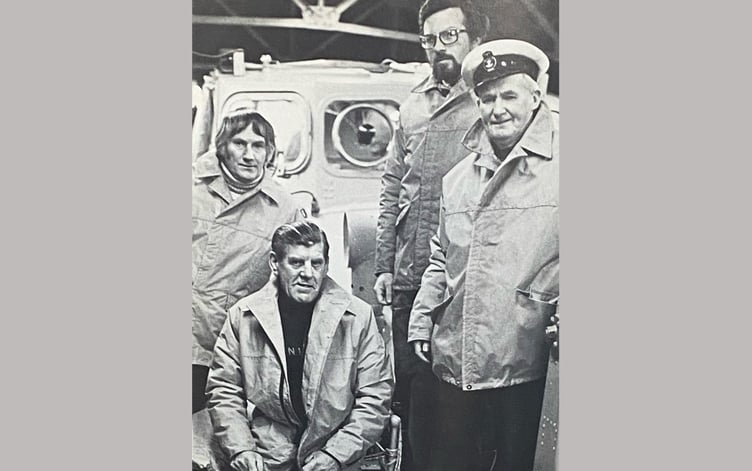

She provided me with a copy of the ‘Sunday Express’ from February 1978 which featured a double-page spread entitled ‘A Special Breed of Men’.

Over the next two weeks I will tell again parts of the story from more than 50 years ago. As we mark 200 years of the RNLI saving lives at sea, it is clearly a time to once again recognise thank the volunteers and recognise their valour.

On Thursday, July 30, 1970 at 11am Bobby Lee watched the departure from Douglas of pleasure boat ‘Mary Anne’ the only vessel to put out to sea on a windswept morning.

He and other boat owners were leaning on the railings and had watched as holidaymakers queued alongside the painted wooden board, rattling in the wind which advertised a ‘scenic pleasure cruise’ to Port Soderick.

John Clague, one of the most experienced Douglas boatmen, helped the last of the 45 passengers aboard the 44ft converted Steam Pinnace and ushered them to the polished wooden bench seats that lined the open decks.

He started the powerful diesel engine and spun the wheel to port, his young crewman ‘Mo’ Mills untied the ropes and pushed off from the sea wall.

‘Next stop Port Soderick.’ Clague told his passengers, before adding ‘hold on it might be a bit choppy today’.

Although the sky was blue with bright sunshine ‘a bit choppy’ was something of an understatement, already the wind was a force 5, gusting to force 6.

Squalls of 30mph and more churned the sea in to confused waved patterns and the passengers squealed in mock horror as they were bombarded with streamers of fine spray.

Only a few miles per hour of wind would push the weather up the Beaufort scale from a ‘strong breeze’ to ‘moderate gale’.

Out of the shelter of Douglas Head, the pleasure craft rolled and pitched violently. The passengers still in holiday spirits expressed ‘oohs and aahs’ as the vessel wallowed over the wave’s crests and into the troughs.

Port Soderick was about half an hour’s sailing time. Once there, the plan was for the trippers to land at the little concrete jetty to spend an hour ashore exploring.

The snack bar would do a brisk trade while others would sit and chat over pints at the plastic topped tables in the bay’s glass fronted hotel.

Then back to Douglas to the boarding houses and cafes in time for lunch.

Not that all would want lunch, certainly not the handful who shuffled miserably to the stern of the boat queasily regretting their bravado in taking to sea.

The vessel travelled towards Little Ness with its steep black cliffs. Far away the sun splintered on the windscreen of a parked car and a solitary figure was seen strolling along the cliff path.

That was the moment the engine cut. One moment it was rumbling healthily, the next nothing.

Clague leaned over and jabbed the starter button with his thumb. The electric motor whirred as it laboured to turn the heavy diesel. But the engine would not fire. Time and again he tried, irritation gradually turning to alarm, but there was no sign of life. Each time the batteries grew flatter.

A woman spoke in a voice spiked with apprehension: ‘Those rocks there, I’m sure we are getting closer to them.’

A murmur of disquiet ran through the boat. Clague straightened up from his fruitless exertions with the engine and looked towards the shore. She was right. The tide was setting out to sea and by itself would have carried the Mary Anne out of immediate danger.

But the spanking breeze was blowing on shore and its force was only sufficient to overcome that of the tide and nudge the boat towards the ‘little eagle’.

Man and boy Clague had sailed these waters. He knew the full horror that would be in store for his passengers and himself if his boat touched the reef.

His face was deadpan as he turned back to his engine. The muttered sounds that passed his lips as he wrestled with the stubborn machinery might have been curses or prayers.

From near the bow of the Mary Anne a man’s voice rang out: ‘There’s a bloke, look on top of the cliff. See if we can get him to go for help.’

And then when the walker waved back: ‘Don’t wave you bloody fool, get help!’

It was it seemed only after an age of waving and shouting that the distant figure turned and began stumbling with maddening slowness up the cliff path towards the parked car.

Back on the promenade Bobby Lee had decided to call it a day. The wind that had put paid to his morning’s business showed no signs of abating. If anything it was freshening.

He decided perhaps he might call for a quick pint at one of the harbourside pubs before walking home.

From across the harbour a motor boat was heading towards him. At the controls waving furiously, was Peter Veale, mechanic of the Douglas Lifeboat.

Bobby coxswain of the rescue boat for 27 years, moved to the harbour steps to meet him.

As the boat’s fenders chaffed against the steps Veale shouted up to the 63-year-old cox.

‘It’s John Clague” He called, ‘He’s in trouble. Some bloke spotted him from the cliffs and phoned the coastguards.

‘Sounds to me as if he lost his engine.’

‘No joke in this weather’ Lee grunted. ‘Where is he?’

‘Heading straight for the rocks at Little Ness.’

‘Oh my god, let’s go!’

Five minutes later the maroons crackled in their distinctive double explosion in the clear skies above the lifeboat station.

A hammer blow parted a steel shackle and 22 tonnes of lifeboat roared the 120ft down the one in eight incline of the slipway to plough into the sea in a welter of foam.

Lifeboats were principally built for endurance, not speed.

Flat out the Douglas boat the RA Colby Cubbin No 1 could push her 46ft 9in bulk along at nine knots, but she would maintain that pace whether in a flat calm or sailing into the teeth of a hurricane. But just for once Bobby wished the tough blue, white and red boat was a little speedier for he knew all about the turbulent currents around Little Ness point.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.