The two and a half years spent in the Wrens, with over half that time on the Isle of Man, deeply influenced former Leading Wren Kathleen Oates’ aspirations and thus what she did with the rest of her life.

Before coming to the Island, Kathleen had worked as a Wren in Liverpool, a wartime showcase for what the world had to offer. There were visits to frigates and corvettes manned by Greek or Yugoslav crews; French conversation lessons with refugee seamen; ice cream and Coca-Cola and dances with US soldiers at the American base. It was a huge eye-opener as to what lay beyond British shores, and sparked a desire in her to see and experience other cultures and horizons.

Hardly surprising then, that she felt only sadness when marking her demobbing anniversary on January 7, 1947. She had spent 1946 regularly thinking wistfully of her time spent on the Isle of Man, and missing her life there with ‘that awful crying ache inside’.

This feeling gradually lifted with time. A couple of Cabin K reunions over the year cemented friendships: she would remain in contact with Cynthia for a good while, and corresponded with the Janes for the rest of her life.

Commencing teaching training in March 1946 and acquiring new skills gave her a focus; a problematic romance with an emotionally elusive ex prisoner of war whom she met at Risley Teacher Training College provided different feelings to wrestle with. This ‘Emergency Training’ College was one of many designed to rapidly train large numbers of new teachers needed, after wartime disruption and the raising of the school leaving age, and offered Kathleen a free course given to ex-Service personnel.

Thankfully, what may have been a rather toxic encounter was over by mid-1947, and diary entries from July show her back at home in Leicester and detail the start of a less complex relationship with Paul, the WW2 pilot who visited her on the Isle of Man, and who would become a British Airways Captain.

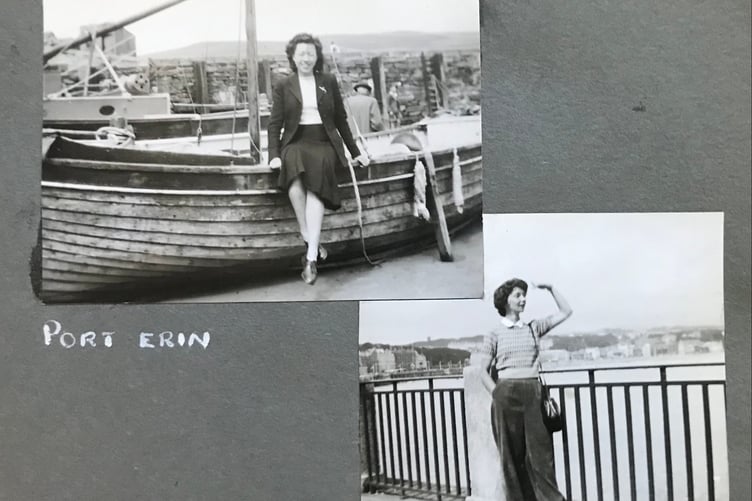

It may have been this background of stability and happy teaching experiences which prompted Kathleen to return with a friend for a nostalgic holiday on the Isle of Man in August 1948. She had not forgotten her ‘beloved’ island, which had filled her dreams and waking thoughts. But still the rest of the world awaited.

Although pilot Paul had wanted to marry Kathleen, January 1950 saw her travel, quite free and single, to Venezuela, to teach the children of Shell employees - finally following up on her desire to see the world.

There, Kathleen enjoyed an ex-pat lifestyle in Maracaibo, sending biscuits and sugar back to Leicester, to help with rationing. She later recalled that some of the European men out in Venezuela were types who had been decorated for bravery in WW2, and who found it difficult to settle back to a more conventional existence in their countries.

Her letters home increasingly mentioned someone called René Smith: he was a petrol engineer working on oil refineries there, and although American, spoke with a French accent. In 1952, Kathleen and René were married.

Raised by his widowed French mother in genteel poverty in Paris, René was sufficiently enraged by the occupation of France to find himself imprisoned twice by the Nazis before he turned 17, for Résistance-type activities, The US Embassy helped extricate him, but René had been told by the German authorities that if caught him a third time, he would be sent to work in Germany. His fearful mother arranged for him to leave France: the Red Cross paid for his train journey to Lisbon and the US Embassy there loaned him money while he waited a month for one of the last civilian ships to repatriate Americans from the danger of the War in Europe, crossing the Atlantic in February 1941.

There, René worked in the New York Van Houten chocolate factory, who broke trade union rules to give this 17 year-old employment, learned English at night and gained a scholarship to Columbia University, where he studied engineering. When American troops entered Paris, his mother ran out to look for her son, as family communication attempts between the USA and France had failed. This was in vain: René had been drafted to the Pacific War with US troops.

His first post after marrying was in Paris, and Kathleen was able to have family to visit them. By 1955, they had moved to the USA and Kathleen wrote home, describing exotica like drive-in movies, and from their hilltop San Francisco flat, witnessing the skyline light up as atomic bombs were tested in the Nevada desert.

Kathleen continued to teach when they relocated to White Plains, N.Y. where their daughter Christine was born - but they soon moved once more with René’s career, in1963, and Christine started kindergarten in Singapore.

The frequent moves of oil company employees put a strain on many marriages: new environments, cultures and languages were challenging to cope with, let alone the strain of leaving family and homes behind – and all this on a regular basis. Kathleen and René’s 21 postings in 31 years ricocheted between different locations in France, Indonesia, Australia, Portugal, Norway, the UK and USA. However, the girl who had so missed her friends from Ronaldsway, had evolved into a self-sufficient woman who thrived on exploring and adapting to new places. Possibly she enjoyed the social anonymity of US ex-pat life compared to the class snobbery so engrained in pre-1960s Britain; also, a very happy marriage was key. They chose to retire to the UK.

Kathleen lived to almost 93 years old, independent and pin sharp to her last day.

Next week’s final article touches on another important connection with the Island, and the visit of daughter Christine and granddaughter Juliette to discover the places Kathleen wrote about, 80 years previously.

.png?trim=0,0,0,0&width=752&height=501&crop=752:501)

.png?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)