In this latest article in the Buildings at Risk series, Simon Artymiuk looks at new discoveries made about the successfully restored Milntown mansion and its background as a home for many centuries of the Christian family. He also looks at the family’s other homes across the water in Cumbria and how they have not fared so well in recent times.

Today, the restoration of Milntown at Lezayre, on the outskirts of Ramsey, as a visitor attraction has been a magnificent success story, providing an opportunity to explore a building which is the nearest the island has to a stately home.

For centuries the estate was the main seat of the Christian family.

However, recent discoveries made by a Manx historian in archives held across the water in Cumbria have revealed that the house is not, as was once thought, a rebuild on the same footprint as the original mansion. Instead has at its heart a ’new’ mid-18th-century farmhouse built on an entirely different site but which reused material from the demolition of the original, somewhat rambling, complex of buildings.

That this discovery was made in Cumbria is entirely appropriate, as the Christian family seems always to have based itself there as well as in the Isle of Man.

Indeed, it is thought - though not conclusively proved - that the Christian family is descended from one Gillocrist (possibly a rendering of the Manx ’Guilley Chreest’ - ’servant of Christ’) who is mentioned in 12th-century documents relating to St Bees Priory - located near the closest point in England to the island - as being a foster brother to King Godred II, one of the Norse Lords of Mann and the Isles. Gillocrist held lands at Maughold, Ballakilley, Baldroma and Balytessayn that later became parts of the Christians’ wider Milntown estate. In the Middle Ages St Bees Priory held the lands near Port Cornaa known as The Barony also later owned by the Christians.

The family’s power in the island was already well established by the 15th century, with a charter of 1408 describing John McCrystyn as ’Justiciarius Insulae’ - a Latin way of saying Deemster - and another charter of that time reveals that John’s son William was one of the 24 members of the House of Keys. The family used the names John, William and Ewan so often that the different generations of earers of these name have to be numbered with Roman numerals.

By the early 1500s John McCrystyn V is recorded as owning land in Lezayre and Maughold plus several mills - a useful asset as islanders had to pay to use these to grind their corn. He also held fishing rights on the ’Alta’ or Auldyn river, which runs down through Glen Auldyn - then known as ’Altadale’ - before passing Milntown. That property, previously owned by the Thwaites family, was bought by John V in 1511. Manx historian Nigel Crowe believes it would have sat within a ’bawne’ - a fortified farmyard with defences against raiders or pirates. It is likely that John V, as a leading member of the Manx community, modernised it to fit his status and to accommodate the five sons and two daughters from his two marriages. The Christians seem always to have produced large families.

John McCrystyn V’s great grandson William VIII, who inherited Milntown in 1539, added the Ronaldsway Estate to its holdings through marriage. His youngest son John became the first Protestant vicar of Maughold and his grandson Edward Christian was the sea captain turned island governor who in the mid-1600s was imprisoned in Peel Castle by James, 7th Earl of Derby and is now seen as a Manx patriot for his championing of land rights.

The change of the family name from McCrystyn to Christian is thought to have happened in around 1568, when William VIII was succeeded as owner of Milntown by his eldest son William IX.

It was this William IX who renewed family connections to the Cumbrian coast by marrying a Culwen relative of the important Curwen family of Workington Hall, a fortified mansion that two centuries later was destined to be owned by one of his Christian family descendants.

William Christian IX’s heir, Ewan X, born in 1579, inherited Milntown at the age of just 14 and spent some years living in Cumberland. He married a Cumbrian girl, Katherine Harrison of Bankfield, Eastholme, but by the age of 26 he had been elected a Deemster in the Isle of Man and remained one for 51 years. Soon after his election he began enlarging and embellishing the Milntown mansion, including adding decorative plaster ceilings and a library fitted out with furnishings of bog oak, and the sheading court for Ayre was often held in the grounds of the mansion, with proceeding conducted in Manx Gaelic.

Ewan X and Katherine had six children, three girls and three boys, the youngest of whom was the Manx patriot William Christian, or ’Illiam Dhone’, destined to be executed by Charles, 8th Earl of Derby, in January 1663 at Hango Hill, Castletown, for his actions during the English Civil War.

We know that Ewan X ended his days in 1655 living at Illiam’s Ronaldsway mansion, but in 1638 he had made an important move as regards the future prosperity of the Christian family by buying the West Cumberland estate of Ewanrigg, also known as Unerigg.

The next heir, Deemster John Christian XI, made further building additions to Milntown in the mid-1660s, after his son Edward XII moved into the mansion with his Westmoreland-born wife Dorothy and their large family of six sons and five daughters. Surviving Manx customs accounts show him ordering old timber for the building work, as well as a dozen chairs, in 1666, along with an even larger quantity of timber in 1668 for ’building and repairing his house’. This was followed by 2,000 lathes onto which wall plaster could be applied.

From the time of the next heir, Edward XII, an inventory of 1675 shows what a rambling house Milntown had become, with two parlours, a hall, ’the late Deemster’s study’, a chimney chamber with loft, outbuildings including a buttery loft, beer buttery, kitchen, milkhouse, milkhouse chamber, store house and cattle-house loft. At about the same time the estate’s holdings grew when the Ronaldsway branch of the Christian family sold Edward the mill at Cornaa.

However, Milntown’s time as the Christians’ main seat came to an end with Edward’s death in 1693. The next heir, Ewan Christian XIII, continued to own it but, having spent much of his childhood living in Cumbria with his mother’s family, he made Ewanrigg his main seat instead.

He subsequently expanded it from a typical Cumbrian defensive pele tower (a legacy of centuries of conflict with neighbouring Scotland) into a mansion boasting fine gardens and views across the Solway Firth.

Nevertheless Ewan XIII and his wife Mary made regular summer visits back to Milntown with five of their daughters, whose beauty was such that they went down in Manx legend as ’The Fair Maids of Milntown’. The majority married wealthy members of the Cumbrian gentry, but the youngest, Alicia, married her cousin the MHK and Captain of the Parish Quayle Curphey, of Ballakillighan. The mill and farm income from Milntown continued to be an important part of the family income and the House of Keys appointed Ewan XIII to be one of their commissioners sorting out the vexed question of the ’straw tenure’ system of landholding when James, 10th Earl of Derby, inherited the Manx Lordship in 1702. The resulting Land Settlement Act, passed by Tynwald in 1704, has been dubbed the ’Manx Magna Carta’.

Earl James later repented that he had agreed to this Act and at one point imprisoned all 24 MHKs for refusing to obey his judicial orders. The next heir to Milntown, John Christian XIV, was chosen to present a petition to the Privy Council in 1723 over this harsh treatment. In Cumbria, meanwhile, John XIV acted as steward and land agent to the Duke of Somerset in both the manor and borough courts of Egremont, close to Ewanrigg. John’s wife Bridget - a member of the Cumbrian Senhouse coal mines family - claimed descent from King Edward I. Their eldest daughter, Mary, married Edmund Law, later Bishop of Carlisle, while Mary and Edmund’s eldest son became Lord Chief Justice Baron Ellenborough.

John XIV and Bridget’s youngest son Charles married Ann Dixon of Moorland Close, near Cockermouth in Cumberland, and was father of Fletcher Christian of Munity on the Bounty fame.

It was John XIV’s eldest son and heir, barrister Ewan Christian XV, who in 1750 made the deal - only recently brought to light through the research of Manx historian Nigel Crowe - to have the old rambling ancestral pile at Milntown demolished and replaced. Nigel discovered the truth in 2014, while looking through documents relating to the Christian and Curwen families at the Whitehaven Archives and Studies Centre. A plan he found there showed that the old Milntown buildings had clearly not matched the footprint of the current one, and he found a contract drawn up between Ewan Christian XV and the estate’s then tenant, the Ramsey-based merchant John Llewellyn.

The contract revealed that as a condition of Llewellyn obtaining a new 21-year lease to Milntown, the merchant would undertake to, within the space of a year, remove ’the old ruined dwelling house’ and build a new Georgian-style farmhouse on a different site. The dimensions of the new house are precisely set out and further conditions stipulate that it should have a staircase with turned balusters ’finished in a handsome manner’, should have windows copied from a sash example that Llewellyn was required to take over to the Isle of Man from Ewanrigg, and that a bedroom and closet over the parlour should be reserved for members of the Christian family when they needed to visit the island.

Ironically, Ewan XV probably never saw the new Milntown house as he died in 1752 at the age of just 34. Having never married, he was succeeded by his younger brother, John Christian XVI. Meanwhile over time Llewellyn extended the new house as his family grew with the birth of five daughters and two sons - perhaps it was down to something in the Glen Auldyn water.

From documents among the Atholl Papers held by Manx National Heritage, we know that John Llewellyn was originally from Bristol yet was proud of his Welsh descent. In 1768 he wrote a grovelling letter to the island’s then Lord, the 3rd Duke of Atholl, requesting a grant of land on the slopes of North Barrule to build the summer residence - now a ruin still known as Park Llewellyn. Other letters reveal that he must have once been involved in the island’s smuggling trade as he had suffered as a result of the 1765 crown purchase of the island from the Atholls with the Act of Revestment.

Another document found by Nigel Crowe in the Whitehaven archives reveals that in 1767 John Llewellyn reached agreement with John Christian XVI to build a new wheat mill at Milntown - perhaps the one still there today. Not long afterwards John XVI died at the Petty France coaching inn near Badminton in Gloucestershire while on the journey homewards from a stay in Bath.

By the time Llewellyn’s 21-year lease expired in 1771, the next heir to Milntown and Ewanrigg, John Christian XVII, was a 15-year-old living under the guardianship of his Cumbrian uncle, Henry Curwen of Workington Hall. This boy, who had inherited his father’s estates at the age of 11, turned out to be the greatest of the Christian family, becoming the only person to be both an MHK and Westminster MP, as well as an important agricultural and social reformer.

His involvement in Manx affairs began in 1773 at his sister Dorothy’s wedding in Dearham Church, close to Ewanrigg. The bridegroom was Captain John Taubman, of Castletown and soon after owner of the Nunnery, and John Christian XVII fell in love with his sister, Margaret Taubman, despite her being six years his senior. He married her at Kirk Maughold in 1775 and a son, also called John Christian, was born but sadly Margaret died after only three years of marriage.

The little boy was subsequently brought up by his Taubman grandparents, while his father recovered from his grief on a Grand Tour of Europe. It involved studies in French language, etiquette and fencing at Douai in France and travels to Switzerland, Germany and Austria that inspired his later agricultural and socio-economic beliefs and innovations. Meanwhile he sent orders to his steward, Charles Udale, at Ewanrigg for the mansion to be further extended and became guardian, along with his elder sisters Bridget and Jane, to his cousin Isabella Curwen, who had become a Ward of Chancery and heiress to Workington Hall following the death of Henry Curwen.

Both Manx National Heritage and the Wordsworth Trust at Grasmere, Cumbria, have transcripts from a diary kept by John XVII’s sister, Jane Christian (later Jane Blamire), in which she recounts events and details of the family’s social life from those times. It often fell to her to undertake sea crossings to the Isle of Man to visit family connections and to the tenants living at Milntown. She mentions staying with the Llewellyns, who by then seem to have moved back to Ramsey, and chatting to Ewan XIII’s still-surviving youngest daughter Alicia Curphey, who was by then believed to be 100 years old but was actually probably in her 80s. Also featuring regularly are members of the Taubman family, either in the island, staying at Ewanrigg en route to the Manx packet boat at Whitehaven, or joining her while in London. She also recounts her brother John XVII’s unexpected arrival back in England ’with fine things from France’ - and the difficulty of getting the teenage Isabella Curwen to concentrate on her schoolwork when she was clearly in love with her widowed cousin. ’She will attend to nothing,’ she writes. ’A most difficult day.’

In 1780, John XVII tried to persuade the Lord Chancellor to allow him to marry his 17-year-old ward Isabella. His former father-in-law, Speaker John Taubman, was one of those who spoke in his favour at a Chancery hearing. When this didn’t work, John and Isabella eloped to Edinburgh and married there where the Lord Chancellor had no influence. Jane Christian’s diary records that she and her sister Bridget danced with the Ewanrigg servants when they heard the news. A month later John and Isabella had another ceremony at Bermondsey, London, just to make sure - and then took Jane and Bridget with them on honeymoon to the South of France.

Following this marriage, Workington Hall became the Christian family’s main seat, with its extensive coal mines adding to the wealth now being accrued to ones on the Ewanrigg estate. The coal was shipped across to Dublin, then reaching its zenith as am elegant and fashionable Georgian city, and the wealth that resulted enabled John XVII and Isabella to remodel the medieval Workington Hall with additions added by the fashionable architect John Carr of York. In 1790 John XVII added the Curwen family name to his own, becoming John Christian Curwen.

John XVII could perhaps be termed an ’Irish Sea Poldark’, as like Winston Graham’s fictional Cornish character he fought off a corrupt dirty tricks campaign by a grasping rival - in this case by James Lowther, Earl of Lonsdale, involving bribery and mob violence - to become Whig Party MP for Carlisle. Like the fictional Ross Poldark he also campaigned for greater rights for the ordinary man, an end to inflated charges for foodstuffs and impositions such as payment of church tithes, Parliamentary reform and an end to the slave trade. He mixed with famous figures such as Edmund Burke and William Wilberforce, and to reinforce a point he once turned up in Parliament dressed in the garb of a Cumbrian farmer, complete with clogs, to demonstrate the hardships they lived under.

John XVII also used the House of Commons to champion the rights of the Manx against impositions being demanded by the 4th Duke of Atholl. Although these efforts were not altogether successful, Christian Curwen was presented with an engraved silver cup as a mark of gratitude.

When it came to his own estate workers and miners, John Christian Curwen set up special funds into which the workers themselves paid a regular contribution and which he himself then contributed a matching or greater sum. Money was then paid out at times of need. Many years later the idea was copied to develop today’s National Insurance system.

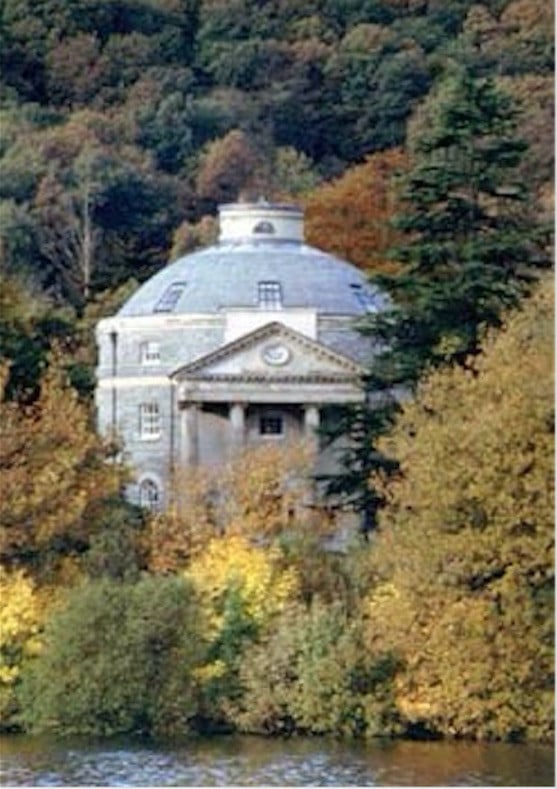

On Windermere, where the Christian Curwens owned the round mansion on Belle Isle, the couple started regular regattas which were attended by George Quayle of Castletown with his yacht Peggy, and at Schoose Farm on the Ewanrigg estate they also started agricultural shows demonstrating new farming methods which were attended by notable figures from all over Britain, including the Isle of Man. A branch of the Workington Agricultural Association was actually set up in the island.

All was not perfect - as with Poldark there were infidelities on John Christian Curwen’s part, as he was always something of a ladies’ man, and his long periods away at Westminster were just as difficult for his wife as BBC viewers have recently seen with Demelza Poldark. Jane Christian’s diary records of Isabella: ’My brother’s long absences grieve her greatly.’

Isabella died in 1820 and in John XVII’s last years the difficult post-Napoleonic Wars climate hit his estate and mine income hard. When he died in 1828, he left only debts to his heirs.

While Workington Hall was inherited by John and Isabella’s children, Milntown and Ewanrigg went to John Christian XVIII, his son born to first wife Margaret. More serious than his father, John XVIII was also more attached to the Isle of Man. After some years practising law in England, and after marrying Susannah Allen in Bath, in 1820 he was invited - ironically by the 4th Duke of Atholl - to become a Deemster and had arrived with his large family back on the island. While for some years they lived at Fort Anne in Douglas, in 1829 the opportunity came at last to return to Milntown. It was John XVIII therefore who was responsible for again making it the family seat and for covering the house built by John Llewellyn with the Gothic ’icing’ and crenellations (rather reminiscent of Fort Anne’s) that are its defining features today.

Meanwhile, the quest to find the location of the ’lost’ original mansion, including a recent archaeological survey, has unearthed some remnants but nothing conclusive about the precise site. Experts’ views on where it might have been differ quite widely, so Milntown continues to hold on to some of its secrets.

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO THE OTHER HOMES OF THE CHRISTIANS?

1. While Milntown is now thriving as an island attraction, the other Christian homes have not fared so well. On the island, Ronaldsway house was demolished in the 1940s to allow airfield improvements that have resulted in today’s airport covering the site. Close by is Hango Hill, where Illiam Dhone met his fate.

2. Over in Cumbria, Ewanrigg fell victim to a fatal decision by John Christian XVIII to make a will dividing his estates among his children. Under the spendthrift heir Henry Christian (who had run off to the South Seas during his youth and had later returned to the Isle of Man with the novelty of a Fijian companion), the house fell into decline in the Victorian period, not helped by Henry’s wife becoming insane. As a result it is said to have inspired the mansion Limmeridge House in Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman In White (earlier this year dramatised by the BBC). Limmeridge is said in the book to be similarly located in Cumberland with views of the Solway Firth, and Collins visited the area with fellow author Charles Dickens in 1857. In the 20th century the top storeys of the once grand Ewanrigg were removed, leaving only a wing as a rundown farmhouse and the remainder of the rest as outbuildings. Now surrounded by Maryport housing estates, not long ago the site was damaged by fire but a developer recently proposed developing it as flats.

3. Workington Hall, meanwhile, was left by the Curwen family to the local council with the aim of it becoming a town hall. This never happened and instead the authority decided to remove John and Isabella Christian Curwen’s 18th century additions to expose the medieval and Tudor workmanship of the original fortified house. This resulted in the building falling into dereliction and today it is a gaunt ruin, while the surrounding land is used as a public park. The buildings of the once celebrated Schoose Farm crown the top of a nearby hill. Fortunately a nearby Georgian townhouse built in 1740 for the Curwen family’s land steward was later left to the town by a benefactress with conditions that it be used for the good of the people of Workington. Now the Helena Thompson Museum, and still free to look around as its namesake required in her will, it has models of Workington Hall in its prime, fragments rescued from the old house, plus displays on that 1568 visit by Mary Queen of Scots (including the ’Workington Luck’, a cup of Italian workmanship she presented as a thank-you gift to the Curwen family) - and an interactive display highlighting John Christian Curwen’s achievements and Manx background.

4. The Belle Isle roundhouse (named after Isabella) on Lake Windermere remained in Curwen family ownership, complete with Christian family portraits and furniture, until fairly recent times but was partially damaged by fire not long after being sold to new owners. Today it is in private hands and not open to the public, but it can be glimpsed from nearby Bowness and boats on the lake.

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.