In the latest Buildings at Risk article, Patricia Newton of the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society (IOMNHAS) looks at the development of Waterloo Road in Ramsey and how some of its 19th century buildings have, from proud beginnings, been through checkered histories or, in recent decades, have disappeared altogether under demolition schemes to become car parks.

A sandstone milestone near Ballure Glen, facing uphill, states ’Douglas XV’; to the north, downhill, another milestone of a different age reads ’Ramsey ½ ml’.

In 1835, a memorial to the Committee of Highways stated that Maughold Street, the main route to Ramsey, was not fit for purpose, with two carts or carriages unable to pass one another; it suggested building a new entrance to the town.

The decision was made to construct a direct line through the Loughs, at the back of the town - in effect a bypass - rather than a route along the shore.

Locally called Cardle Road after Cardle’s (near Corrany) owner, Robert Kerruish was the first to drive a carriage along the new route.

Kerruish may have had little inkling of the future role the road would have in the development of the town’s public life, and of the later play that its official name ’Waterloo Road’, together with its continuation as Albert Row, Street, Road and Square, might have on the fate of its associated buildings.

Whether you were Protestant, Presbyterian, Wesleyian or Roman Catholic, or attending church or chapel, grammar, board or day School, and favouring temperance or alcohol or simple amusement, all needs were catered for along the road, accompanied by rows of mainly terraced housing, businesses, a bank and finally the electric tramway bringing in visitors in their hundreds and encouraging them to stay.

So what has happened to this vibrant scene?

With the northern tip of the island being only 16 miles from Scotland (closer than it is to Douglas), perhaps it’s not surprising that probably the earliest building in Waterloo Road was that of the local Claughbane stone and steeply pitched slated roofed church that the Wigtown Presbytery of the United Secession Church were asked to build to accommodate 230 people.

It opened in April 1837 but was superseded in 1885 by the Scotch Kirk, or Trinity Presbyterian Church, designed by Mr Barry and built by Boyde Brothers.

The older building became a temperance hall in 1886 and was subsequently bought by the Quayle Trust, which also administers adjoining houses.

As one of Ramsey’s oldest surviving buildings, today’s Quayle’s Hall has been appropriately renovated by The Rotary Club of Ramsey into the Ramsey Heritage centre.

But what of its successor?

With a dwindling congregation, Trinity United Reform Church is now being offered for sale, its future in doubt.

The Scots were followed by Wesleyian Methodists. Two earlier chapels in south Ramsey had successively become too small (and have been demolished).

In 1845, Rev Samuel Taylor, superintendent minister, gained permission from the Secretary of the Methodist Conference to build a chapel 58ft long by 50ft broad to seat 750 on land given by Mr W Callister, of Thornhill.

It was stated that the opening debt should not be more than £400.

Starting an association with four generations of the family, James Callow helped build the chapel, which opened on June 5, 1846.

In 1862, vestries were added, and in 1882, an additonal 24ft extension was made for 300 new sittings. In 1906, the building was entirely reseated, the rostrum altered and the organ put back, a vestibule was built and new windows put in. In 1938, it was reroofed - but by 2018 it, too, was up for sale.

In past times education and religion went hand in hand.

Various private schools already existed but, prior to the implementation of the 1872 Education Act, education was not free.

Ramsey already had its grammar school built in 1762, but until funds were raised in the 1860s, a new school could not be built. However, in 1864 the Manx stone new school, now referred to as the Old Grammar School, had its foundation stone laid in part of Joe’s Lough, appropriately by Lieutenant Governor Henry Loch.

It was constructed in a non-Manx style with stone mullion windows - a feature that is reflected in the adjacent former almshouses, Mysore Cottages.

Competition with later Wesleyan schools meant the Grammar School did not achieve sufficient funds or endowments for maintenance, repairs or improvements.

With his Latin motto of ’Nil amante difficile’ - in effect ’Where there’s a will there’s a way’ - Rev A S Newton remedied the situation, moving the school to larger premises in north Ramsey.

However, the impact of the 1900 Dumbell’s Bank Crash eventually saw a move back after both parents and Newton lost out financially.

Later, as an entity the Grammar School was extended into the Wesleyan Day School but, fortuitously, the old Grammar School remained, being turned into Ramsey Youth Centre in 1952.

Albert Street and Road schools had a different fate.

George Kay designed, and James Callow built, both the yellow-brick Wesleyan Day and Sunday School for 550 scholars in 1888, and then the 1902 St Maughold’s Roman Catholic School opposite for which Father Barron had strenuously raised funds and which, curiously, had a dedication stone of Russian granite.

While the former school served as an overflow for the 1905 Albert Road School when it was extended, that did not save it from meeting its own ’Waterloo’ in the early 1990s.

A similar fate was met by the younger building opposite, with only a gatepost now remaining.

The biggest car park of all was left by the 2011 demolition of the Albert Road School, which in its time had been described as one of ’the most up-to-date schools in the island’.

The purpose-built Dumbell’s Bank, in reality entitled Douglas and the Isle of Man Bank (Dumbell, Son & Howard), on the corner of Peel Street, was erected by another Callow in 1889, its ornamentation reflecting the quality and success the bank was then associated with.

After the 1900 crash, it became Parr’s Bank and then the National Westminster until November 1988, with only the word ’BANK’ disappearing from its frontage.

However, its existence clearly had an impact for business in the vicinity, particularly after the opening of the electric tramway into Ramsey in 1899 when numerous adverts appear for local businesses, which were almost next door to it and opposite the tramway’s Palace Station.

Just opposite, on December 2, 1899, Messrs Chrystals Brothers advertised the sale of the late Dr Clucas’s 1847-vintage ’well-built genteel residence (with surgery), coach house, stables, harness room and yard’.

With the complex of buildings comprising over 300 sq yds, the potential for business purpose was recognised.

By 1909, Nelson’s Waterloo Hotel and Dining Rooms was advertised as ’The Home of the Cyclist’.

Perhaps this was not considered propitious,and by the 1920s its name was changed to Hotel Britannia.

But its sprawling and expansive past caught up with it and, as at present, dogged it, as then proprietess, Miss Bond, became bankrupt.

Meanwhile, the road’s most southerly building, the Albion Hotel, later Ascog Hall, at the junction with Stanley Mount West, was by the late 19th century waiting to accommodate visitors, but was in time used by volunteer army units and Scouts. It is now converted into apartments.

Described as being in the ’very heart of Ramsey and in a most popular and largely frequented thoroughfare’, and also completing the crossroads of the big four streets, in February 1892 McAdam & Moore were appointed contractors to build The Ramsey Palace.

Measuring 90ft long, 74ft wide and 50ft high, and located in the garden of Elm Villa ’endowed with a luxuriant growth of trees and ornamental shrubs’, it was an entertainment venue aimed at providing a similar place of amusement to Douglas’s.

Fifty workmen were employed on its construction.

Opening concerts in July 1892 were highly praised, but the sacred concert staged in August was condemned by, among others, the Trinity Presbyterian Church.

However, Friendly Societies such as the Foresters also held their meetings here.

At the outset the local press considered that ’the people of Ramsey had been so long without any source of amusement that is has become almost impossible to get the inhabitants to turn out’.

Tey were perhaps not encouraged by the fact that ’the establishment would be run on strict temperance principles’.

With the venue boasting a splendid oak floor, and being lit with electric light and capable of holding 1,200 people, by the end of 1892 The Palace was in financial difficulties and was put up for sale in January 1893.

Ramsey Amusements Ltd redesigned the building in 1895 more along the lines of a modern cinema, and renaming it The Plaza.

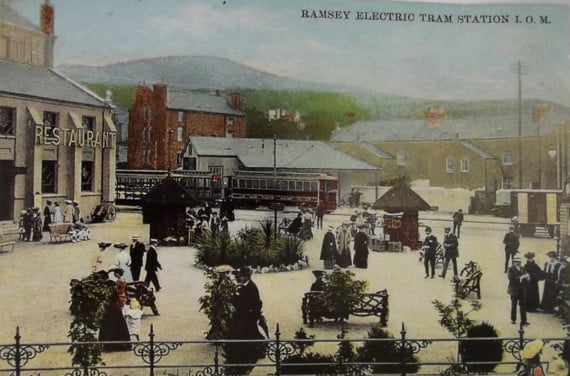

But the name Palace stuck and, four years later, when the Manx Electric Tramway arrived in the town of Ramsey itself, its terminus was named Palace Station.

Its proximity, where ’many thousands of visitors arrive and depart weekly’, was an important selling point for businesses.

For example, No 12 Albert Row - ’The Deemster’s House’ - was advertised as being of special attention to those intending to set up first-class refreshment premises.

The Isle of Man Times’s northern branch also had premises opposite the tramway station, as did promoters of Vannin Sliver Lead Mining Co of Glen Auldyn, whose secretary, William Rowe, was younger brother of Capt Richard Rowe of Laxey Mines.

In 1935 the Palace Cinema, as the venue was being described then, was given a pure geometric makeover to become the Plaza.

That year the film reels for the first ’Mutiny on the Bounty’ movie arrived in Ramsey in a snowstorm after havingfirst travelled to Laxey by tram, then back to Douglas by boat, and then had eventually arrivedvia Glen Helen by car.

But the Plaza still had its operating restrictions which, in writing his revue ’Let’s make Whoopee’ for The Northern Players, the Rev E C Paton poked fun at as follows:

’I flew from Blackpool the other day

’To spend a Sunday here;

’I ordered lunch at your best hotel,

’And asked for a glass of beer.

’The waitress looked at me aghast;

’She said "You must be mad!

’We can give you cocoa, pop or tea,

’But beer, it can’t be had.’

But for the Palace or Plaza, its own ’Waterloo’ arrived in 1991, when a car park took its place.

As for Palace Station, where both the initial station building and its tram shed were originals relocated from Ballure, where the line had initially halted on the edge of Ramsey in 1898 before being extended into the town itself a year later.

Between them in recent times these buildings accommodated the Royal Carriage (used to transport King Edward VII in 1902) and the Planet loco from the Queen’s Pier, as well as a youth centre and a small museum.

However, following refusal of planning consent for a combined bus and tram station on the space - there simply was not enough room on the station site for both to safely operate and pedestrians to circulate - the government carried on its destruction of buildings in this part of Ramsey and demolished both structures.

Now the tram terminus has been ignominiously moved to behind the Ramsey Methodist Centre and the station site proper mostly lies empty - how this is meant to attract passengers to the scenic northern stretch of the line and help reinvigorate Ramsey as a whole has not been explained.

Car parks, albeit free, are winning over quality brownfield redevelopment on these government-owned sites.

Yet, as illustrated, during its 1946 centenary the Waterloo Methodist Chapel congregation left a time capsule message for those residents and visitors still around in 2046.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.