The son of a Manxman who served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War has talked about the effects of the war on his father, Bill, writes Paul Hardman.

Bob Young has shared a letter which he wrote about his father Bill, who served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and returned to the island with post-traumatic stress disorder – an understudied condition at that time.

What Bob described as ‘prolonged PTSD’ culminated in his father committing suicide in 1986, hanging himself at the age of 64.

He said that he wanted to get his father’s story out there and show that among the wartime tales of glory, there were many stories of the survivors, which did not end ‘happily ever after’.

Bill was born in Douglas in 1921, and also signed up there for the Royal Navy in 1938.

He served on vessels ranging from gunboats to frigates, in regions across the globe – including on the deadly Arctic convoys.

Returning to the island post-war, he would go on to work as crew on the Steam Packet ships Manx Maid, Lady of Mann and Manxman.

Bob’s parents married at Braddan Church and had three children, but he said that the traumas his father experienced between the ages of 18 and 24 had ‘stayed with him for life’ as he tried to readjust to peacetime society.

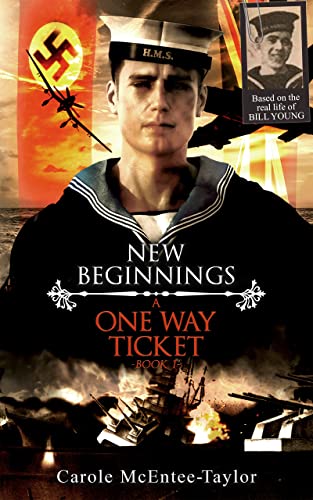

Four books have since been based on William’s story by author Carole McEntee-Taylor, the first called ‘A One Way Ticket’.

Bob’s letter reads:

My brother Stephen and I were enjoying our third pint in the Foresters Arms in the beautiful little village of Dunster, Exmoor, when we started talking about our dad.

To us, Dad was a sad, lonely figure, especially to me as I remember him being rarely sober and his decision making had brought about a sad life, mainly through alcohol.

Steve had befriended Dad in the mid 70s, and he said he had seen another side of him.

Dad was a lost soul. Bitter and not loved by anyone.

Steve saw him from time to time and found him a ‘character’.

This meant he told Steve great stories that the normal man in the street couldn’t possibly tell. Dad couldn’t relate to the neighbours of Bowness Road [Manchester] who were clerks and bus drivers throughout the war and worked in engineering firms or the cigarette factory up Oldham Road when he was fighting.

He would tell Steve about the war years and colourful periods of his life in the merchant navy, the scraps and fights he got into and the constant brushes with the law he had from being a schoolboy to the week before when he had been caught stealing from Woolworths while drunk.

He also told Steve about swimming ashore from a sinking ship in the Red Sea, being sunk twice more, once in Tobruk harbour and also while minesweeping in a requisitioned trawler.

I was able to tell Steve of the horrible early morning drunken visits that involved a lot of shouting, broken front window and door, police taking him to the Middleton cells for the night.

I also showed Steve the scar I had from a knife being wielded on one occasion.

One time he knocked two policemen over on the way to the Panda car. Steve was able to tell me about Dad eating only a pan of food in a week.

He would put chicken backs in the pan and unpeeled veg and boil it and eat it over the next seven days. Couple of scoops a day.

First thing in the morning he would wake up and have a cigarette and a barley wine before starting the day. Dad was skinny and very wiry as he had been all his life.

We had a laugh about the stories we told each other and then Steve mentioned Dad would have qualified for the Second World War’s Arctic Star medal (recently issued to recognise servicemen who sailed the Arctic convoys to Russia).

Churchill called it ‘the worst journey in the world’.

My knowledge of Dad’s war was confined to the comments he would make to us on his drunken early morning visits in the 1960s.

We didn’t pay a lot of attention to the content of what he was saying as our overriding feeling was of being upset and seeing Mum angry and the constant ‘they have seen nothing’ referring to me and my younger brothers and that didn’t really mean anything to us.

He would also talk about the Stuka bombers coming down and gesture how they flew and sounded as they dropped their bombs and how he saw his shipmates’ bodies all over the ship.

Heads over there, legs over there.

This didn’t mean a lot to lads in their early teens.

When he had calmed down and the shouting had stopped and the police were on their way he would quietly say “we are all on a one way ticket” meaning we are all on our way to die.

I told Steve I would look into getting the Arctic Star.

I remember Mum getting replacements for the five other medals Dad was awarded because he had swapped the originals for a bottle of wine in Mexico after the war.

We remembered Mum had told us Dad had been sunk on three ships.

But we didn’t know when or where or the names of the ships.

I wrote to the Ministry of Defence for his service record, then applied for the Arctic Star.

I received Dad’s service record and for the first time in my life I realised he had been in the war from day one till the last day.

Volunteered in 1938 as a 17-year-old.

Had spent the ages from 18 to 23 at war at sea and one year either side preparing for war or mopping up the U Boats after the war and it started to make sense to me that ‘we had seen nothing’ in our lives like he had said.

The realisation Dad had done his bit for the freedom we have all enjoyed since 1945 made me start thinking about what was behind those early morning visits, his comments and his anger at the system.

Maybe more about PTSD than alcohol?

At first the Ministry of Defence said he wasn’t entitled to the Arctic Star until I was able to establish HMS Keats was part of Operation Goodwood that had the task of destroying the German battleship Tirpitz in a Norwegian Fjord.

Basically, an operation that was looking for trouble, whereas hard as the Arctic Convoys were, they were trying to avoid trouble.

I wrote to the Ministry of Defence telling them HMS Keats was on Operation Goodwood and many men were lost in the failed attempt to destroy the Tirpitz.

HMS Keats was the screen for the Canadian aircraft carrier HMCS Nabob which lost 36 men.

I received a phone call from the Ministry of Defence who said they would send the Arctic Star.

I had tears coming down my face during the phone call as I felt ashamed and proud at the same time.

-24.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.